PRODUCT AS PROTAGONIST: The Ester Story

In 1893, the late Victorian publisher Andrew Tuer released a book featuring an incredibly long name and an equally impressive craft. Christened "The Book of Delightful and Strange Designs Being One Hundred Facsimile Illustrations Of the Art of the Japanese-Stencil-Cutter", Tuer’s book is a catalog of sorts, offering an introduction to the Japanese art of katazome for his European readership.

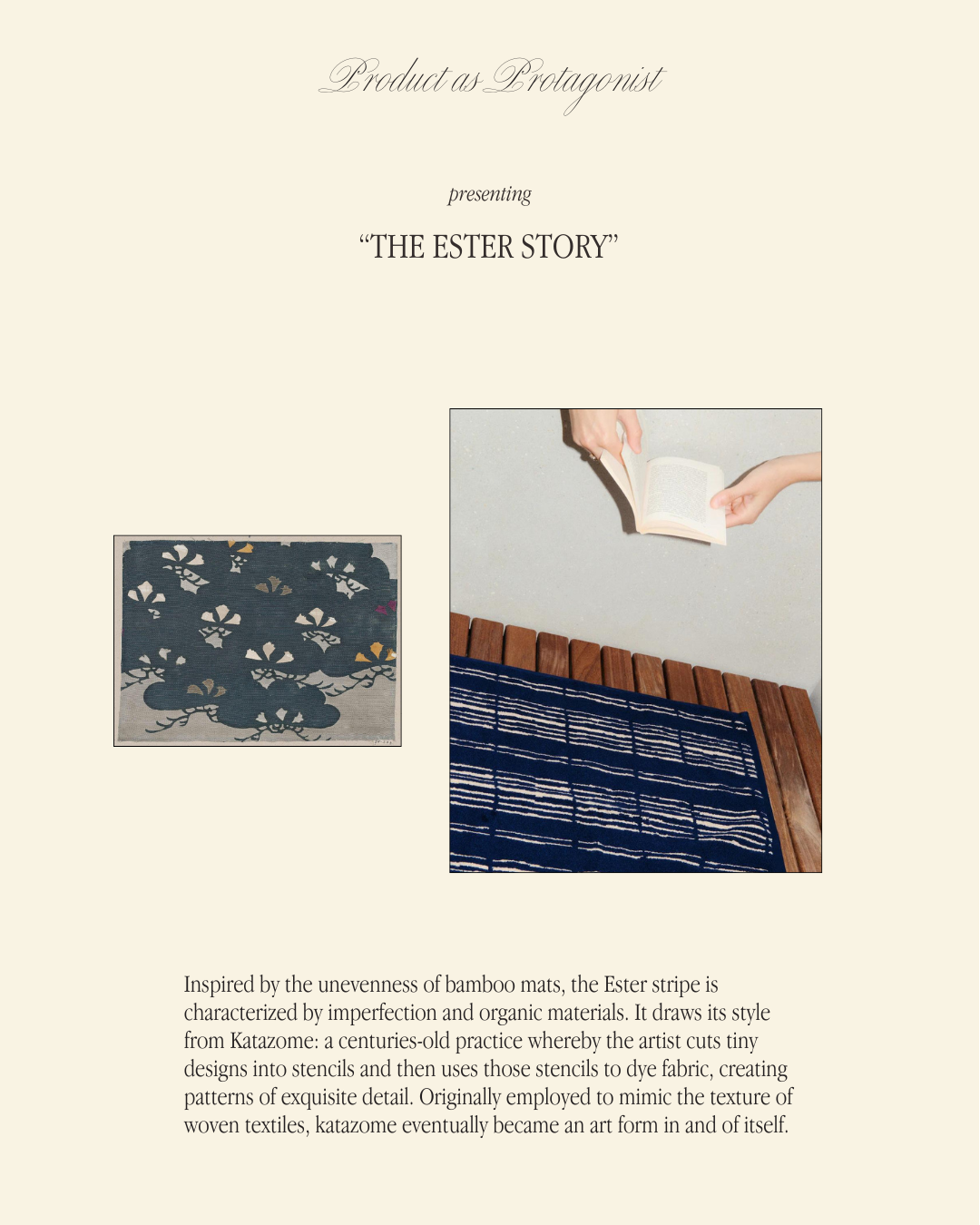

Katazome is a centuries-old practice whereby the artist cuts tiny designs into stencils and then uses those stencils to dye fabric, creating patterns of exquisite detail. Originally employed to mimic the texture of woven textiles, katazome eventually became an art form in and of itself.

As you might imagine, stumbling across this old book was akin to discovering literary gold. In it, we found a stripe unlike any other. Inspired by the unevenness of bamboo mats, this stripe is characterized by imperfection and organic materials. It breaks up the monotony of the basic stripe. It is Ester.

Ester honors the imperfection of the human hand as exemplified by katazome – though, to be sure, katazome is very nearly perfect.

But what about other stripes? Ester is in dialogue with a whole host of designs, geographies, and artifacts – past and present. Consider Europe, the very place where Tuer published his landmark book.

In the Middle Ages, stripes were associated with people on the margins – think prisoners and social outcasts. Later, the stripe surfaced during the French Revolution as a symbol of protest. And later still, stripes became the official uniform of French sailors in 1858, because a striped Breton shirt made it easy to spot someone who was lost at sea.

The history of the stripe is a history of contradictions: symbolizing both unity and division, both order and upheaval, the stripe, contrary to appearances, is never simple. The stripe, rather, is what you make of it.

Consider what you might make of Ester, our first (but, mind you, not our last) stripe.